by Phyllis Raybin Emert

by Phyllis Raybin Emert

The treatment of Native Americans since America’s founding has been riddled with betrayal and broken promises. In July 2020, with a 5-4 vote, the U.S. Supreme Court held the U.S. to at least one of the promises it made to Native American tribes.

In McGirt v. Oklahoma, which was combined with another case, Sharp v. Murphy, the Court decided the fate of Jimcy McGirt and Patrick Dwayne Murphy, both Native Americans who committed brutal, vicious acts, and were convicted and imprisoned after Oklahoma state court trials. The cases are about McGirt and Murphy, but the U.S. Supreme Court decision is more about jurisdiction, and whether past Indian treaties signed by the federal government are still in effect and should be honored.

Both McGirt and Murphy argued that their crimes were committed on Native American land, specifically Muscogee (Creek) Nation land, and therefore their cases should have been tried in either federal court or in a Creek tribal court, since the state did not have jurisdiction over them. For Murphy, convicted of murder and sentenced to the death penalty, a win at the U.S. Supreme Court means that he escapes a death sentence, as a federal court would not be able to sentence a Native American to death if the crime was committed on tribal land.

In the Supreme Court’s majority opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote, “Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.”

First, some history

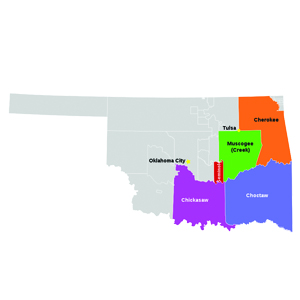

In the 19th century, there was an intense effort by federal and state governments to make tribal land available to white settlers who wanted to grow cotton in the Southeastern part of the United States. This resulted in a series of forced relocations of Indian tribes, starting in 1830 when President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law. The government signed treaties with what were called The Five Nations (the Creek, the Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Chickasaw and the Seminole Nations). In exchange for land west of the Mississippi River in what was then the Oklahoma territory, the members of these nations would leave their homes in the Southeast.

These forced resettlements, which started in the winter of 1831, were known as the Trail of Tears and often took place with little notice, supplies or protective clothing for the Native Americans. Food was not provided and towns and villages generally ignored the travelers along the way. The Trail of Tears stretched for more than 5,000 miles and included portions of nine states (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Tennessee). According to military records, more than 100,000 indigenous people were forced from their homes and marched the Trail of Tears. More than 15,000 did not survive the journey, succumbing to exposure, starvation and disease.

Native Americans did not sit idly by while the government tried to take their land. They fought in the courts, making it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. With Worcester v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1832 that the state of Georgia did not have the right to impose regulations on Native American land, affirming that they are sovereign nations “in which the laws of Georgia [and other states] can have no force.” The opinion, written by Chief Justice John Marshall, stated: “…treaties and laws of the United States contemplate the Indian territory as completely separated from that of the states; and provide that all intercourse with them shall be carried on exclusively by the government of the union.” In other words, because they are considered nations, only the federal government, not states, could govern them.

President Jackson refused to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision and the states ignored it. Despite the fact that it was not enforced, Worcester v. Georgia is credited with establishing the foundation of tribal sovereignty.

Back to the 21st Century

Matthew L.M. Fletcher is a professor at Michigan State University College of Law and director of its Indigenous Law and Policy Center. The key question in McGirt v. Oklahoma and Sharp v. Murphy, Professor Fletcher says, was whether the two men’s crimes were committed on Indian land or on land under the jurisdiction of the state of Oklahoma. The U.S. Supreme Court decision in favor of Native Americans was “surprising” to Professor Fletcher, who sits as the chief justice of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Supreme Court, but “correctly decided,” in his opinion.

“The rule is that only Congress can terminate an Indian reservation,” Professor Fletcher explained. “Congress never terminated the Creek reservation. Still, Oklahoma has been acting as if the reservation no longer existed for more than a century. Many non-Creek citizens live there and own land there. But the law is the law.”

The dissent

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his dissenting opinion that the Court’s decision would “wreak havoc and confusion on Oklahoma’s criminal justice system.” According to the Chief Justice, “the state’s ability to prosecute serious crimes will be hobbled and decades of past convictions could well be thrown out.”

In response, Professor Fletcher says, “It is true that the tribal and federal criminal cases have doubled or tripled. But the Chief Justice’s belief that the decision will impact the state’s ability to prosecute cases is just false.”

Professor Fletcher says that the tribe and the state of Oklahoma have been cooperating on reservation law enforcement matters for decades, and the impact of the Court’s decision should be minimal.

In the Court’s opinion, Justice Gorsuch wrote, “We do not pretend to foretell the future and we proceed well aware of the potential for cost and conflict around jurisdictional boundaries, especially ones that have gone unappreciated for so long. But it is unclear why pessimism should rule the day. With the passage of time, Oklahoma and its Tribes have proven they can work successfully together as partners.”

In fact, after the Court’s decision was announced, Oklahoma’s Attorney General released a joint statement with the Five Tribal Nations saying that they had “made substantial progress toward an agreement to present to Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice addressing and resolving any significant jurisdictional issues raised by [McGirt].”

Professor Fletcher admits that a few state prisoners will be let go, assuming they bring a suit against Oklahoma seeking release, but most of them “will be quickly charged by the federal government.”

In the podcast, This Land, Professor Fletcher addressed this issue. “If you don’t raise your jurisdictional claim early on in your criminal case, you lose it forever,” Professor Fletcher stated in the podcast. “Even if it means that you spend 50 years in jail from a court that didn’t have jurisdiction over you, you lose that right to make that claim.”

After the Supreme Court’s decision, Jimcy McGirt and Patrick Dwayne Murphy were both indicted in federal court for their crimes. Both are being held without bail. Professor Fletcher points out, “there is no parole from federal prisons, so neither men would likely ever see freedom in their lifetimes.”

The implications

While the landmark decision focused on the Creek nation, Professor Fletcher says it was expected that it would affect the other four tribes as well, since they are “similarly situated.” This means that a little over 40 percent of Oklahoma, nearly 19 million acres, is now officially considered Indian Country.

Nearly two million people live on that land and estimates are that only 10 to 15 percent of them are Native Americans. So, how will the Court’s decision affect the non-Native Americans living in Eastern Oklahoma’s Indian Country?

“Not much,” Professor Fletcher says. “Tribes generally do not possess powers over non-Indians. The biggest impact is on criminal jurisdiction over Indian persons, which shifts from the state to the federal government and the tribes.”

Concerns were also raised about what the decision would mean for education in the state. Shawn Hime, the executive director of the Oklahoma State School Boards Association, told EdWeek, “In Oklahoma, our tribes have great relationships with our local school districts. I don’t anticipate anything changing with those relationships.”

In the end, as Justice Gorsuch wrote in the opinion, the Court’s decision boiled down to a promise that was made and should be kept.

“On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise,” Justice Gorsuch wrote in the Court’s decision. “Forced to leave their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama, the Creek Nation received assurances that their new lands in the West would be secure forever….Both parties settled on boundary lines for a new and ‘permanent home to the whole Creek nation,’ located in what is now Oklahoma. The government further promised that ‘[no] State or Territory [shall] ever have a right to pass laws for the government of such Indians, but they shall be allowed to govern themselves.’”

Discussion Questions

- How do you feel about the Court’s decision in the case? Was it correctly decided in your opinion? Explain your answer.

- Native Americans were forced to leave their homes on orders of the U.S. government. During World War II, the U.S. government forced Japanese Americans to leave their homes as well. Compare and contrast the experience of both ethnic groups. What are the similarities? What are the differences?

- How would you feel if your government did that to you and your family?

- How do you feel about the way Native Americans have been treated in this country?

Glossary Words

convicted—to be found guilty of a criminal offense either by the verdict of a jury or the decision of a judge.

dissenting opinion — a statement written by a judge or justice that disagrees with the opinion reached by the majority of their colleagues.

indict — to charge someone with a criminal act.

indigenous—native to the land.

jurisdiction — authority to interpret or apply the law.

majority opinion — a statement written by a judge or justice that reflects the opinion reached by the majority of their colleagues.

sovereign — indisputable power or authority.

sovereignty — supremacy of authority over a defined area or population.

This article originally appeared in the spring 2021 issue of Respect, the NJSBF’s diversity newsletter.