by Michael Barbella

by Michael Barbella

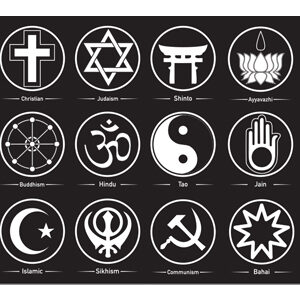

In freedom of religion cases, the issues usually come down to a balance between the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause and its Free Exercise Clause. The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion (Establishment Clause), or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; (Free Exercise Clause).

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment has been interpreted to mean that the government cannot support one particular religion over another religion or support religion over no religion. The First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause says that the government cannot prohibit citizens from practicing their religious faith.

You’ve probably heard the phrase “separation of church and state” to explain the Establishment Clause. The words “separation of church and state,” however, don’t actually appear in the U.S. Constitution. The phrase is attributed to a letter that Thomas Jefferson wrote in reply to the Danbury Baptists in 1802. As a religious minority, they were concerned that there was no explicit protection of religious liberty in Connecticut’s state constitution. In his letter President Jefferson referred to the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause and contended that it built “a wall of separation between Church and State.”

Over the years the U.S. Supreme Court has been called on a number of times to decide freedom of religion cases. The Court decided one such case, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, in June 2020 and will issue an opinion in another case, Carson v. Makin, in 2022.

What’s this about?

In May 2015, Montana enacted an alternative school voucher program intended to boost support for private education. The program authorized the use of public funds to help finance alternative or private K-12 schools. Specifically, the Montana law provided a tax credit to donors of “innovative educational programs” at public and private non-parochial schools. The statute capped tax credits at $3 million, with no more than $150 going to any individual child.

In administering the voucher program, Montana’s Department of Revenue established an administrative policy that barred the tax credits from being used for attendance at a religious school. The Department based its policy on a Montana state constitutional provision which says: “The state shall not make any direct or indirect appropriation or payment from any public fund or monies…for any sectarian purpose to aid any church, school, academy, seminary, college, university, or other literary or scientific institution, controlled in whole or in part by any church, sect, or denomination.” This language comes from the Blaine Amendment in the Montana State Constitution.

What’s a Blaine Amendment?

Named after U.S. Representative James G. Blaine of Maine, the language of these amendments varies by region. After hearing a speech delivered by President Ulysses S. Grant, where he defended public education and attacked sectarian schools, Representative Blaine proposed a federal constitutional amendment in 1876 that would have expanded the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause to prohibit state funding for religious schools. The amendment passed the House of Representatives but failed in the Senate; however, many states adopted the language of Blaine’s amendment in their state constitutions. Montana is one of 37 states whose state constitution contains a Blaine Amendment. New Jersey’s state constitution has no such provision.

Although Blaine amendments were steeped in the anti-Catholic bigotry that was prevalent in the late 1800s, their purpose evolved over the years to be seen as a protection of religious liberty, as Jonathan A. Greenblatt of the Anti-Defamation League told The Washington Post in 2017.

“These constitutional provisions serve significant government interests—leaving the support of churches to church members, while also protecting houses of worship against discrimination and interference from the government,” Greenblatt said.

Espinoza

In December 2015, the Department of Revenue’s policy spurred a legal challenge from three mothers, including Kendra Espinoza, whose name is on the case. They wanted to use the scholarships at a private Christian school and sued Montana’s Department of Revenue, alleging its rule discriminated based on both their religious views and the sectarian nature of their chosen academy, Stillwater Christian School.

In March 2016, a district court judge sided with the mothers, contending that the Department of Revenue misinterpreted Montana’s constitution. The district court ordered the office to discontinue enforcement of the policy; however, the Department of Revenue appealed the decision to the Montana Supreme Court, contending the tax credit program was unconstitutional without the policy. The higher court agreed and reversed the lower court decision in December 2018. The Montana Supreme Court, however, invalidated the program for all schools, religious or otherwise, based on the state’s constitutional provision.

In its 5-2 ruling, the Montana Supreme Court said, “When the Legislature indirectly pays general tuition payments at sectarian schools, the Legislature effectively subsidizes the sectarian school’s educational program. That type of government subsidy in aid of sectarian schools is precisely what the delegates intended Article X, Section 6, to prohibit.”

What the U.S. Supreme Court said

Six months after the Montana Supreme Court decision, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case, garnering national attention for its potential implications on education policy and funding. Conservative groups and religious organizations have long advocated for equal treatment of faith-based education, but teachers’ unions and civil rights groups have argued against it, claiming such equity could endanger public school funding.

The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately reversed the Montana Supreme Court’s decision in June 2020, deciding the lower court’s interpretation of the policy violated the U.S. Constitution’s Free Exercise Clause. The Court considered Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia Inc. v. Comer as binding precedent in deciding the case, rejecting the Montana Department of Revenue’s notion that its no-aid policy promoted religious freedom. In the Trinity case, decided in 2017, the Court said that denying religious institutions access to a state-funded program that repaved playground surfaces violated the First Amendment.

“We have long recognized the rights of parents to direct ‘the religious upbringing’ of their children. Many parents exercise that right by sending their children to religious schools, a choice protected by the Constitution. But the no-aid provision penalizes that decision by cutting families off from otherwise available benefits if they choose a religious private school rather than a secular one, and for no other reason,” Chief Justice John G. Roberts wrote for the majority in the Espinoza decision. “A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

Perry Dane, a professor at Rutgers Law School—Camden, who teaches courses on religion and the law, says that the U.S. Supreme Court had a stricter interpretation of the Establishment Clause in the past than it does now.

“For example, the Court has allowed states to let parents direct some state monies to religious schools as part of a general program sending money to other private schools,” Professor Dane says. “More recently, the Court has gone further. It has ruled that, in some cases, the Free Exercise Clause forbids states running such programs from discriminating against religious private schools. That was the issue in Espinoza.”

Even though the Montana Supreme Court suspended the program, according to Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion, that didn’t absolve the state of wrongdoing. Nixing the Tax Credit program did not promote religious freedom, as Montana had argued, but rather constituted “discrimination against religious schools and the families whose children attend them,” the chief justice wrote.

In his dissent, Justice Stephen G. Breyer warned his fellow justices against an “overly rigid application” of the Free Exercise and Establishment clauses, noting that such an interpretation could spawn conflicting mandates that eventually would defeat their basic purpose.

“It may be that, under our precedents, the Establishment Clause does not forbid Montana to subsidize the education of petitioners’ children,” Justice Breyer wrote. “But the question here is whether the Free Exercise Clause requires it to do so. The majority believes the answer to that question is ‘yes.’ The majority’s approach and its conclusion in this case, I fear, risk the kind of entanglement and conflict the religion clauses are intended to prevent.”

That conflict, though, might very well stem from the Court’s struggle to remain neutral in religious matters. “These cases and others suggest the [U.S.] Supreme Court is increasingly focusing on the neutrality principle in its understanding of the religion clauses,” Professor Dane says. “The challenge, though, will be to enforce that principle in a way that continues to recognize the importance of separation of religion and state as a bedrock commitment of the American Constitution.”

Another case in Maine

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments on December 8, 2021, in another freedom of religion case. This one, Carson v. Makin, concerned the state of Maine, which has a system in place to provide an education for students in rural parts of the state if there is no public high school available. If a public high school is not an option, the state will pay up to $11,000 toward tuition at a private school, provided the school is not religious. You may be thinking that the issue seems the same as the one in Espinoza. The subtle difference is that while the Court’s ruling in Espinoza determined that it was unconstitutional to block religious schools from public funding simply because of their religious status, Carson will ask the Court to rule whether it is also unconstitutional to exclude religious institutions because it would fund religious activity, such as teaching a particular religion or religious philosophy.

For example, the two schools at issue in Carson are Bangor Christian School and Temple Academy. In court documents, Maine alleges that both schools discriminate against people of other religions, as well as LGBTQ students and teachers. Temple Academy, according to the court filings, “will not admit a child who lives in a two-father or a two-mother family” and the school requires its teachers to acknowledge and accept that “God recognizes homosexuals and other deviants as perverted.”

LGBTQ advocates are concerned that a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs in the Carson case would mean that taxpayer money would be funding discrimination, which violates the Maine Human Rights Act. According to reporting in Christianity Today, both schools “because of their biblical principles” would not “accept tuition assistance from the state if doing so would mean adhering to Maine’s Human Rights Act.”

In an opinion piece for The Washington Post, Rachel Laser, president of Americans United for the Separation of Church and State, wrote, “Each of us should get to decide how—and whether—to support religion. People of faith, and those of no religion, should not have to support the inculcation [instilling] of beliefs with which they disagree. It is up to parents and religious communities to educate their children in their faith. Publicly funded schools should never serve that purpose.”

The Court is expected to issue its ruling in Carson v. Makin in June 2022.

Discussion Questions

- How do you feel about the Court’s decision in Espinoza? Should a state be required to subsidize religious education? Why or why not?

- What do you think about the two schools in the Carson case? Should they have the right to hire and admit whoever they want based on their “biblical principles” even if those principles discriminate? Explain your answer.

- What do you think about the separation of church and state? Is it important? Why or why not?

Glossary Words

appealed— when a decision from a lower court is reviewed by a higher court.

non-parochial— not relating to a church or parish.

plaintiff — person or persons bringing a civil lawsuit against another person or entity.

precedent — a legal case that will serve as a model for any future case dealing with the same issues.

reverse— to void or change a decision by a lower court.

sectarian—associated with a particular religion.

secular — not sacred or concerned with religion.

statute—legislation that has been signed into law.

This article originally appeared in the winter 2022 edition of The Legal Eagle.