by Robin Roenker

by Robin Roenker

Recently, voters in New York City used ranked-choice voting (RCV) to select the winner of the Democratic primary race for mayor. While New York may be the largest U.S. city to have adopted this form of voting, it’s not alone.

According to FairVote, a nonpartisan vote-reform advocacy group, 22 jurisdictions in the U.S. currently use ranked-choice voting for certain types of elections, with 53 more prepared to adopt the voting method in upcoming elections. In 2020, five states (Alaska, Hawaii, Kansas, Nevada and Wyoming) used ranked-choice voting in the Democratic primary for President of the United States.

Maine is currently the only state using ranked-choice voting for congressional and presidential elections, though Alaskans recently voted to adopt the system for statewide federal elections beginning in 2022.

How does ranked-choice voting work?

In an election, the majority wins, right? Actually, plurality voting is the most common electoral system used in the U.S. In plurality voting, also known as winner-takes-all voting, the candidate who receives the most votes wins; however, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the candidate won by a majority.

For example, let’s say there are three candidates running for office. For our purposes, let’s say Candidate A receives 40 percent of the vote, Candidate B receives 35 percent of the vote and Candidate C receives 25 percent. With 40 percent of the vote, Candidate A would be the winner because they received a plurality. Candidate A did not, however, receive a majority of the vote, which would be more than 50 percent.

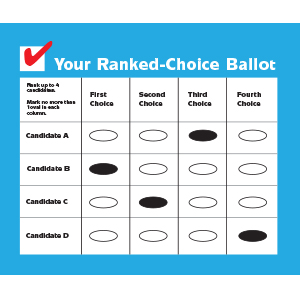

Unlike plurality voting, where voters vote for a single candidate, ranked-choice voting allows voters to rank the candidates in order of preference, noting their first choice, second choice, third choice and so on. In ranked-choice voting, if a single candidate receives a majority of voters’ top choice votes, then that candidate wins. If there is no majority winner, in other words, if no candidate achieves more than 50 percent of first choice votes, then the candidate that received the least number of votes is eliminated. Voters who listed the eliminated candidate as their first choice will have their votes reallocated to their second-choice candidate. This process continues until a single candidate achieves a majority of the votes.

Critics of plurality voting point out that elections with more than two candidates can result in electing a candidate that received a minority of the votes cast. For instance, in a contest with four nominees, to win a plurality, a candidate would only need a little over 25 percent of the vote.

While ranked-choice voting is gaining attention due to its use in recent high-profile elections like the New York City mayor’s race, it’s not new. According to the Ranked Choice Voting Resource Center, a division of the Election Administration Resource Center, a nonpartisan election policy nonprofit, ranked-choice voting has been used around the world, in various formats, since its invention in Europe in the 1850s. In the U.S., ranked-choice voting was used in local elections by dozens of cities from the 1930s to the 1960s, when it fell out of fashion.

According to Craig Burnett, a political science professor at Hofstra University, all voting reforms are cyclical.

“It forces everyone to ask themselves, ‘How should your version of democracy produce winners?’” Professor Burnett says.

Is ranked-choice voting legal?

Some detractors of ranked-choice voting argue that it violates the “one person, one vote” principle, meaning that individuals should have equal representation in voting. The principle stems from several voting rights cases in the 1960s, primarily the U.S. Supreme Court case Reynolds v. Simms (1964), which dealt with the size of electoral districts. The decision of the Court said that electoral districts must be roughly equal in population so that one district does not have more representation than another.

Critics of RCV claim the system gives a single voter multiple votes, thereby violating the “one person, one vote” principle. Proponents of RCV contend that the system still gives each voter a single vote because only the vote in the final round counts. The technical term for this is called single transferable vote. So far, lower courts have upheld the legality of ranked-choice voting systems with cases such as Stephenson v. Ann Arbor Board of Canvassers (1975) and Minnesota Voters Alliance et al. v. the City of Minneapolis (2009).

More recently, in Maine, several legal attempts to overturn the usage of ranked-choice voting have been dismissed. In 2018, Maine State Rep. Bruce Poliquin filed a lawsuit (Baber et al v. Dunlap) in federal court to block the state’s use of ranked-choice voting in federal elections, claiming the voting system violates the U.S. Constitution. That same year, a federal judge in Maine upheld the constitutionality of the ranked-choice approach. In 2020, both the Maine Supreme Judicial Court and the U.S. Supreme Court denied efforts by the Republican Party of Maine to block usage of ranked-choice voting in the state’s presidential election.

Similarly, in July 2021, Anchorage Superior Court Judge Gregory Miller ruled against attempts to block ranked-choice voting in Alaska, determining that the state’s newly adopted RCV system is legal. That ruling opens the door for RCV to be used there for the first time in a general election in 2022, although the plaintiffs in the case plan to appeal to the Alaska Supreme Court.

Advantages of ranked-choice voting

“Ranked-choice voting gives voters a chance to provide a fuller expression of their preferences among candidates, says David Kimball, a political science professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Essentially, advocates argue that RCV reduces the risk that two candidates with broad, overlapping support will split the vote, allowing a third candidate who lacks majority support to win the election. This is what is called a “spoiler” candidate. It is when a third-party candidate enters the race and splits the vote, drawing votes away from an ideologically similar main party candidate, which unintentionly helps the candidate with an opposing viewpoint gain a larger percentage of the vote in the process.

Proponents also believe that ranked-choice voting may lead to campaigns with less polarization and name-calling among candidates, creating a deeper focus on real issues. The theory is that rather than focusing on only a select group of voters for whom they are the top choice, to have the best chance at winning a ranked-choice election, candidates also need to appeal to voters for whom they might be a second or third choice.

“A plurality-style voting system where there’s only one winner and everyone else loses really encourages attack-style politics,” Professor Kimball says. “It encourages negative campaigns.”

In addition, RCV could eliminate “lesser-of-two-evils” voting. In most general elections, there are only two viable candidates—Republican or Democrat—which sometimes leads to voters choosing the candidate they dislike the least.

Disadvantages of ranked-choice voting

Even proponents of ranked-choice voting admit that the process is more involved than traditional voting.

“The biggest argument against ranked-choice voting is that it’s a more complicated task,” says Professor Kimball. “There’s also newness there, which might be confusing to voters, so you have to explain the rules and how it works.”

Teaching voters how to rank order candidates on the ballot – and encouraging them to do enough research about candidates to be able to knowledgeably form preferences – takes substantial voter education. Some research suggests these challenges can lead to lessened voter participation by disadvantaged or marginalized voters when ranked-choice voting is used.

“If you’re working two jobs, or if you have a family and your first concern is about making sure there’s food on the table, voting may not be at the forefront of your mind – and you may not have time to sit and think in-depth about your voting preferences,” says Professor Burnett.

Additionally, research has suggested that highly educated voters are more likely to fill out ranked-choice ballots in full – rather than choosing only one candidate – and that the process, as a result, disadvantages less educated voters.

“A key practical criticism [of ranked-choice voting] is that if people are confused by the system, they may just not turn out to vote altogether,” says Ken Kollman, a political science professor at the University of Michigan.

While ranked-choice voting has both detractors and proponents, Professor Kollman says there is no such thing as a perfect voting system.

“There are a lot of very bad voting systems that don’t last very long, because people realize right away that they are bad,” Professor Kollman says, and notes that “ranked-choice voting is well-liked by people who study voting.”

Discussion Questions

- As the article points out, critics of RCV contend that it violates the “one person, one vote” principle, while proponents of the system say it does not and voters are still only casting one vote. Which argument do you find more compelling? Explain your answer.

- Professor Kimball says that plurality voting encourages attack-style campaigns. How do you feel about that? What measures do you think could be taken to promote more positive political campaigns?

- How do you feel about plurality voting, where the winner does not need to gain a majority of support from voters?

Glossary Words

appeal — a request that a higher court review the decision of a lower court.

jurisdiction — authority to interpret or apply the law.

nonpartisan— not adhering to any established political group or party.

plaintiff — person or persons bringing a lawsuit against another person or entity.

plurality voting—a system of voting that requires the winner to have a greater number of votes than other candidates, but not necessarily a majority.

This article originally appeared in the fall 2021 edition of The Legal Eagle.